Ortho Case: Shoulder Injury

Author: Victor Huang, MD

Case: A 30-year-old-male presents to the Emergency Department for right shoulder pain after a motorcycle accident. The patient has no medical problems and does not take any medications. He was helmeted and denies any head injury, loss of consciousness, neck pain or any other complaints. Vital signs are stable and the primary survey is intact. The secondary survey is remarkable for right shoulder held in adduction and internal rotation, with inability to range the shoulder. The neurovascular examination is normal distal to the injury.

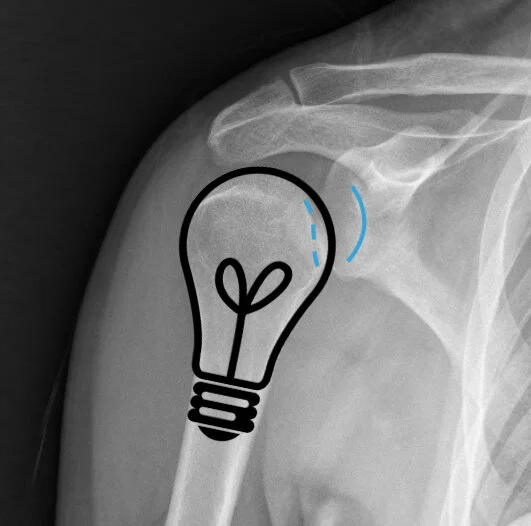

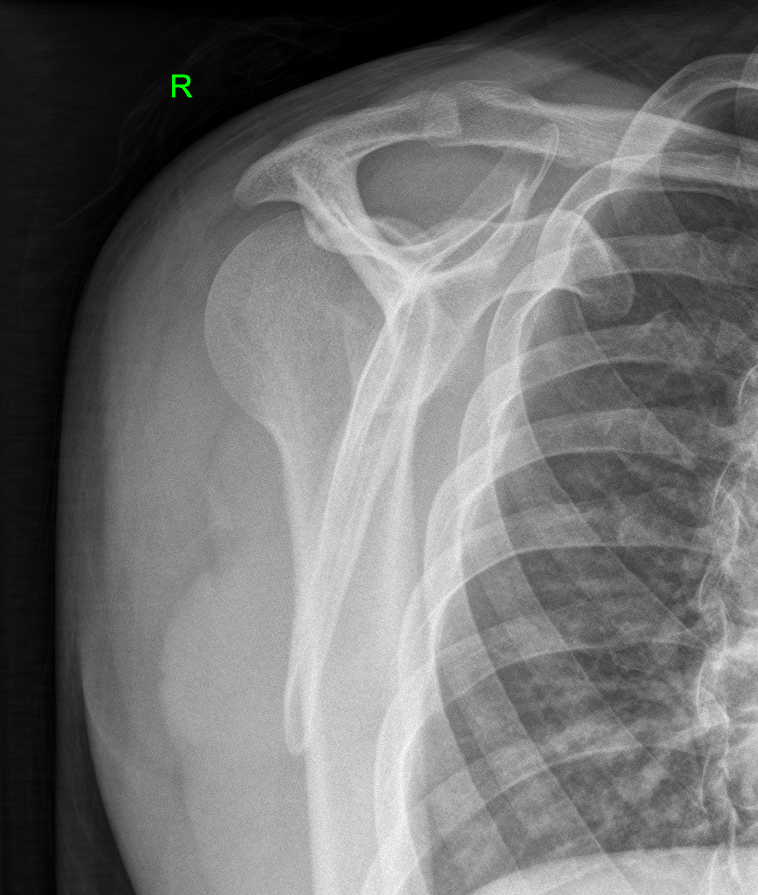

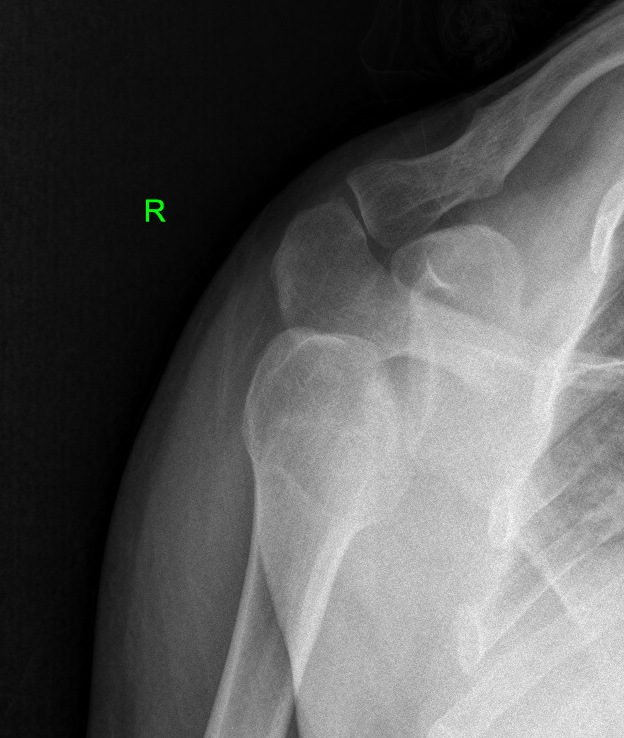

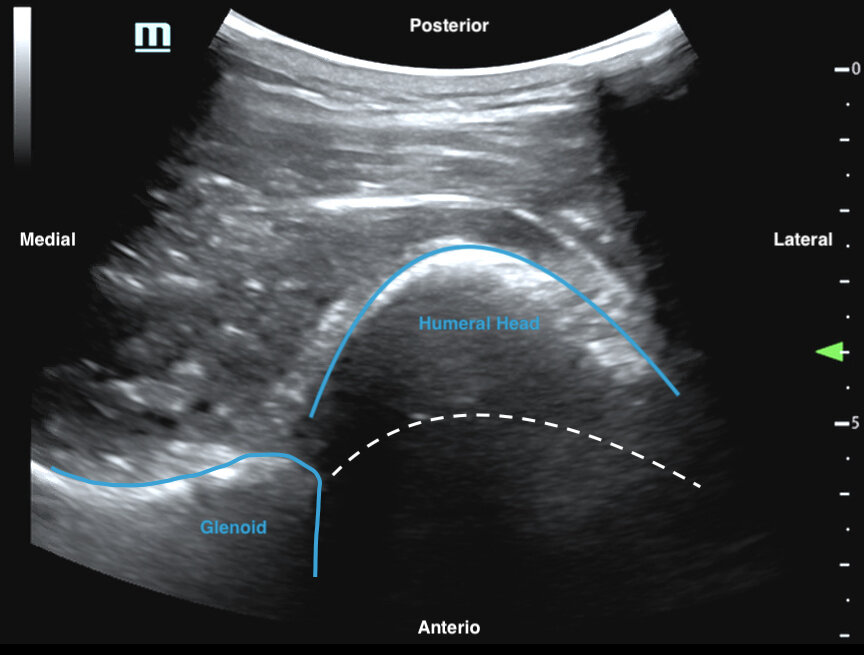

Figure 1 A-C: Image prompt. Plain radiographs of the right shoulder - AP, scapular Y, and axillary views. Author’s own images.

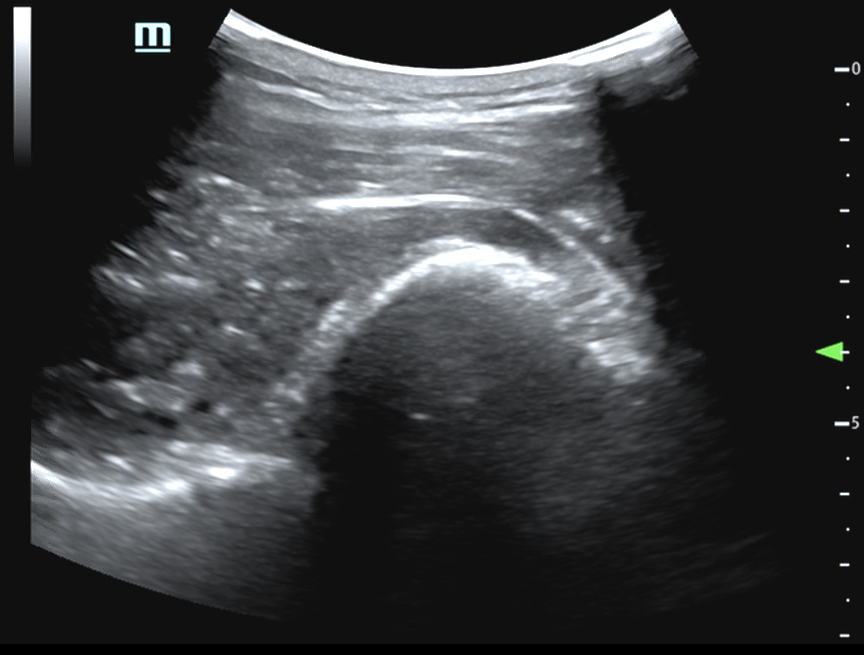

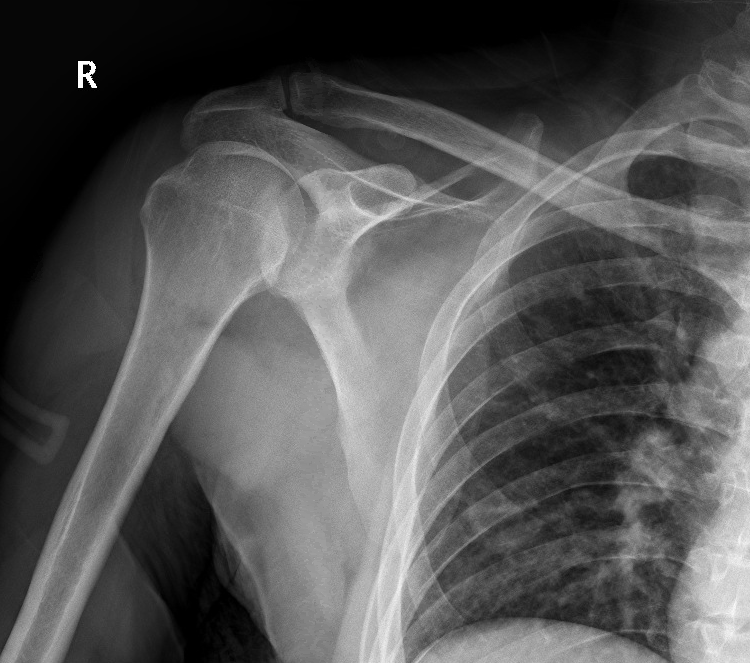

Figure 2: Ultrasound images of right shoulder that demonstrate posterior dislocation of the humeral head relative to the glenoid. The dotted white lines indicate the normal position of the humeral head. Author’s own images.

What is the diagnosis and management in the Emergency Department?

See below for answers!

Case Resolution:

Plain radiography of the right shoulder (Figure 1) shows a posterior shoulder dislocation with an impaction fracture of the humeral head. The AP view demonstrates subtle signs with widened glenohumeral joint space and decreased overlap, lightbulb sign, and impaction deformity of the humeral head. The ultrasound image (Figure 2) shows that the humeral head is dislocated posterior relative to the glenoid.

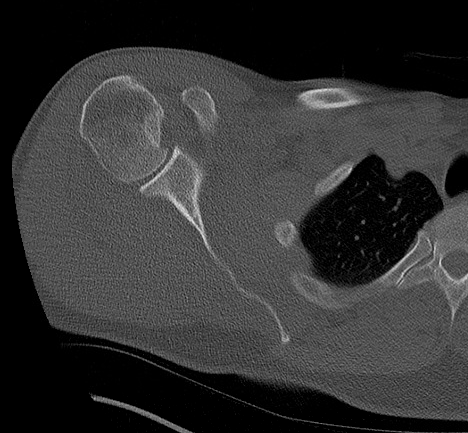

Orthopedics is consulted. The patient received an intra-articular lidocaine 1% injection to provide local anesthesia. Propofol 1 mg/kg was utilized for procedural sedation to facilitate the reduction. Traction-countertraction reduction maneuver was used in the supine position. Traction was applied on the adducted and internally rotated arm, and posterior-to-anterior pressure was placed on the humeral head. Reduction elicited a palpable clunk and a return of shoulder range of motion. The shoulder is immobilized in a sling. Post-reduction x-ray shows a reduced glenohumeral joint and CT shows a reverse Hill-Sachs deformity. The patient is discharged in a sling for outpatient Orthopedic management.

The patient underwent successful nonoperative management with sling immobilization followed by a progressive rehabilitation program. He has subsequently returned to physical activity without any limitations.

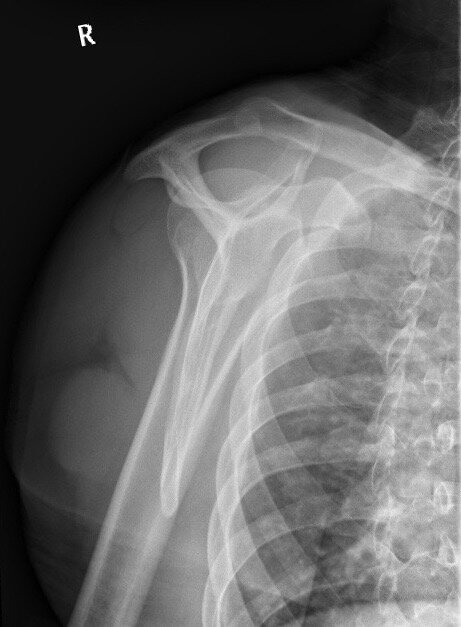

Figure 3 A-B: Post-reduction radiographs - AP and scapular Y view demonstrating improved alignment of previously dislocated glenohumeral joint, with redemonstration of impaction fracture of the humeral head.

Discussion:

Posterior dislocations are rare and account for less than 4% of all shoulder dislocations.1-6 The angulation of the scapula and the strong soft tissues posteriorly likely protect against posterior dislocation.3,5

It is very important for Emergency Physicians to have increased awareness and a high degree of suspicion for posterior shoulder dislocations because the diagnosis is missed on the initial evaluation in more than 50% of cases, and may not be recognized for weeks or even months.2,5,6 This delay in diagnosis increases the risk of complications including articular cartilage injury, avascular necrosis, arthropathy, and functional impairment.2,5,6 Other complications include fractures of the glenoid and proximal humerus, labral injury like reverse Bankart lesions, rotator cuff tears, posterior shoulder instability, recurrent dislocations, and degenerative joint disease.1-5

The mechanism of injury is usually traumatic (67%) or due to convulsive seizures (31%).2 Dislocation may occur from a direct force applied to the anterior shoulder, or after a fall on an outstretched hand with the shoulder flexed, adducted, and internally rotated.1,2,4,5,6 Meanwhile, seizures and electrical shock cause sudden contraction of the internal rotator muscles that overpower the external rotators and drive the humeral head posteriorly, which can result in either unilateral or bilateral dislocations.1-6

The patient will usually present with shoulder pain and difficulty with range of motion. The shoulder will be held in adduction and internal rotation, with limited abduction and external rotation.1,2,4,5,6 Inspection and palpation demonstrates a prominent coracoid process anteriorly, loss of the anterior shoulder contour, and rounded shoulder posteriorly with a palpable humeral head.1,2,4,5,6 Clinical evaluation is limited in the postictal period as the patient often cannot localize their complaints and the physical examination is unreliable.6

Imaging should include plain radiography with three views of the shoulder, because a single AP film may appear normal and miss a posterior dislocation.2,5,6 Subtle findings on the AP film include a “lightbulb” appearance of the humeral head held in internal rotation, increased distance between the anterior glenoid rim and the humeral head (rim sign), decrease in the half-moon overlap of the glenoid fossa and the humeral head, and an impaction deformity of the anteromedial humeral head (trough sign).4-6 Thus, it is essential to obtain orthogonal views, like axillary, lateral scapular Y, or Velpeau view.1-6 Posterior dislocations are easily seen on axillary views, but obtaining this view is often difficult due to restricted abduction.1,2,6

Computed tomography (CT) imaging provides characterization of the size of articular surface defects and associated fractures of the glenoid and humeral head.1-3 This is important for determining nonoperative versus operative management and preoperative planning.1,2

Orthopedics should be consulted in the Emergency Department because posterior dislocations are rare, difficult to reduce, and have a high-incidence of associated injuries.6,7 Neurovascular compromise, though uncommon, is an indication for immediate reduction.1,5

Procedural sedation and intra-articular injection of local anesthetic should be used to achieve adequate muscle relaxation and analgesia for the reduction (Daya, Reichman, Curtis, Jacobs).2,4,5,7

The patient should be in supine position with sheets looped around the axilla and antecubital fossa.6,7 Traction-countertraction should be applied on the adducted and internally rotated arm, and anteriorly-directed pressure should be applied on the posterior aspect of the humeral head.4-7

After reduction, repeat neurovascular examination and imaging should be performed.6 The shoulder should be immobilized in a sling, but splint immobilization in external ration and slight abduction may be required if there is post-reduction instability.4,5

Nonoperative treatment is indicated for stable reduced dislocations with small articular defects less than 25% of the articular surface.1,3 This includes sling immobilization for 3 to 6 weeks, followed by rehabilitation with range of motion then strengthening exercises, with eventual return to sport in 4 to 6 months.4

Indications for surgical intervention include irreducible dislocations, “locked” posterior dislocations, and certain associated fractures.3-5 Articular defects between 25% - 40% are usually managed with reconstruction, and large defects greater than 40% with shoulder arthroplasty.1,3

Figure 4 A-C: Axial, coronal, and sagittal CT images that demonstrate interval reduction of right shoulder dislocation, which is now anatomically aligned. Impaction fracture along the anterior humeral head (Reverse Hill-Sachs compression deformity).

Works Cited:

Guehring M, Lambert S, Stoeckle U, Ziegler P. Posterior Shoulder Dislocation with Associated Reverse Hill-Sachs Lesion: Treatment Options and Functional Outcome After a 5-year Follow-up. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2017;18(442):1-7. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1808-6.

Jacobs RC, Meredyth NA, Michelson JD. Posterior Shoulder Dislocations. BMJ. 2015;350(h75):31-32. doi:10.1136/bmj.h75.

Rezazadeh S, Vosoughi AR. Closed Reduction of Bilateral Posterior Shoulder Dislocation with Medium Impression Defect of the Humeral Head: A Case Report and Review of Its Treatment. Case Reports in Medicine. 2011;124581:1-4. doi: 10.1155/2011/124581.

Curtis RJ. Glenohumeral Instabilities. DeLee & Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009: 932-946.

Daya MR, Bengtzen RR. Shoulder. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014: 618-642.

Horn AE, Ufberg JW. Management of Common Dislocations. Roberts & Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014: 954-998.

Reichman EF. Shoulder Joint Dislocation Reduction. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2013: 531-549.

Image: Pixabay. Available at: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/light-bulb-lighting-electric-341059/. Access on February 19, 2020.